Notes to myself

An effort to extend the time between the recently learned and soon forgotten

April, 2016

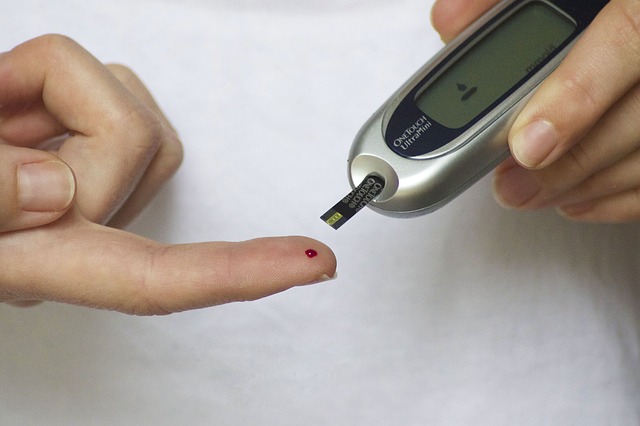

Sleep and sugar

Our circadian rhythms of sleep and wakefulness have profound impacts on our physiology. We both consume food and burn calories primarily while awake, and not surprisingly most of the pathways regulated by circadian rhythms are therefore involved with metabolism (Panda, 2002). Diabetes and other metabolic diseases are therefore closely tied to the processes that pertain to wake/sleep cycles, and this connection hold clues that may help to address these disease states.

For example, the number of hours spent a sleep each night can influence the development of type 2 diabetes and other mortality risks. Repeated episodes of inadequate sleep (<6 hours) not only decrease glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity, but can alter hormone levels (leptin levels decrease while ghrelin levels increase) leading to hunger and perhaps obesity (Spiegel, 2005). Too much sleep ( > 9 hours) has also been associated with diabetes (Chaputa, 2009) and all-cause mortality (Cappuccio, 2010), though the variability in these data are greater and the physiological explanations less clear. As well there is abundant evidence tying late-night shift work to obesity and diabetes, but these data are strictly epidemiological (Kivimaki, 2011).

Much clearer is the demonstration of an association between the gene for the melatonin receptor 2 (MTNR1B) and fasting plasma glucose levels (a key indicator of diabetes). In the Meta-Analysis of Glucose and Insulin-related traits Consortium (MAGIC), a variant in the MTNR1B locus provided the single strongest association with fasting glucose across the entire genome (p=10^-215). In this and subsequent studies the index variant (rs10830963) was found to commonly be associated with higher fasting glucose, and as well with the development of both gestational diabetes and type 2 diabetes. It is uncommon to find such a strong association in a reasonably high frequency variant (roughly 30% of Europeans are heterozygotes). One of the connections between the sleep data and MTNR1B may be melatonin.

Melatonin is a key mediator of biological rhythms in the body. It is produced predominantly at night, with production during the day dropping to very low levels. Melatonin has a wide variety of physiological consequences, altering both hormone release and neuronal firing. Different melatonin receptors can respond to melatonin by promoting either vasoconstriction or dilation, lowering cortisol secretion, and modifying glucose uptake. The melatonin receptors MTNR1A and MTNR1B are expressed in the brain, particularly in areas associated with circadian rhythms. Many tissues that are targets of insulin also express MTNR1B, among them adipocytes, muscle cells, and hepatocytes (Florez, 2016). Critically, the MTNR1B receptors in pancreatic beta cells may cause individuals with the risk variant to secrete less insulin in response to normal levels of melatonin in the body, which could be at the root of the increase of T2D among these people.

This information could point the way towards therapeutic interventions. If the melatonin receptor system in beta cells could be selectively blocked then insulin secretion could be increased. Individuals carrying the risk variant might be more sensitive to the insulin-inhibitory impact of melatonin. Further study is needed, and in particular measuring plasma melatonin and insulin levels in people with and without the MTNR1B risk variant rs10830963. Naturally any such studies should be carefully controlled for time of day and season to reflect the rhythmic variability among these two hormones.

Image credits:

Journal references:

- , Sleep Duration and All-Cause Mortality: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Prospective Studies, Sleep. 2010 May 1; 33(5): 585–592. PMCID: PMC2864873

- , Sleep duration as a risk factor for the development of type 2 diabetes or impaired glucose tolerance: Analyses of the Quebec Family Study, Volume 10, Issue 8, September 2009, Pages 919–924, doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2008.09.016

- , The genetics of Type 2 Diabetes and Related Traits, Springer International Publishing, 2016. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-319-01574-3

- , Shiftwork as a risk factor for future type 2 diabetes: evidence, mechanisms, implications, and future research directions., PLoS Med 8, e1001138, doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001138

- , Coordinated transcription of key pathways in the mouse by the circadian clock, Cell 109:307-320

- , Sleep loss: a novel risk factor for insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes, Journal of Applied Physiology November 2005 Vol. 99 no. 5, 2008-2019 DOI: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00660.2005