Notes to myself

An effort to extend the time between the recently learned and soon forgotten

January, 2017

Sources of instability

Some may find it soothing to view Trump’s election victory as a fluke, or at least as an event that is not indicative of larger changes. Such a view may be incomplete, however, and future elections may lead to additional surprises. Systemic societal changes are underway in the United States, and we would do well to try to understand them.

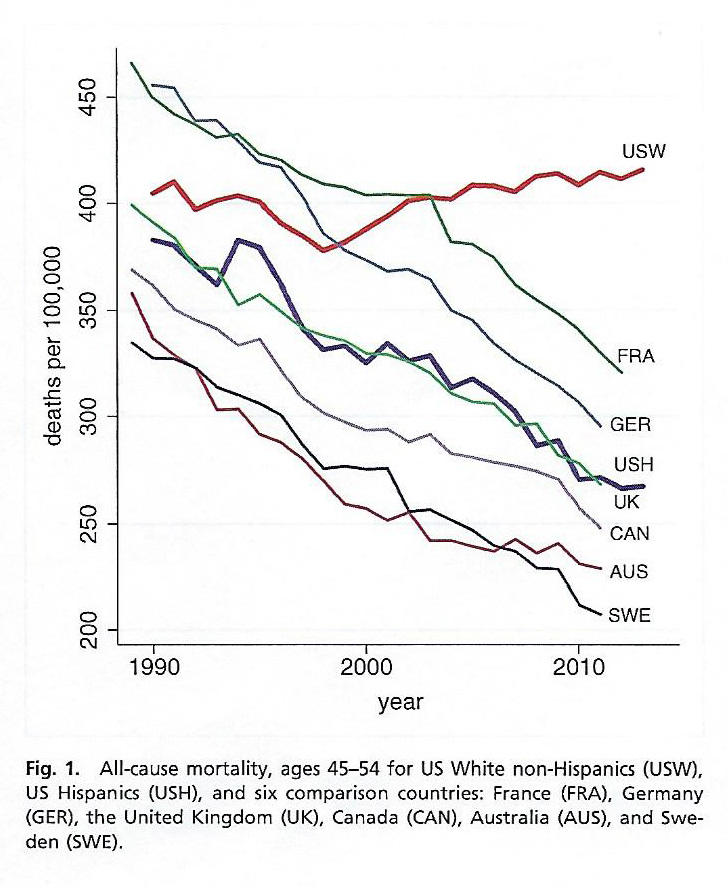

Consider the recent changes in mortality among middle-age, white, non-Hispanic Americans. Among most rich countries between 1998 and 2013 mortality rates declined by roughly 2% per year, continuing a general decline in mortality since the 1950s. The same trend in declining mortality was observed for most age groups and non-white ethnicities in the United States. Among middle-aged white non-Hispanics, however, overall mortality rates over the same period rose by 0.5% per year. The causes of death driving this reversal were primarily suicide, drug and alcohol poisoning, and chronic liver disease.

The numbers of people involved in these changes are large, and the aberrations highly statistically significant. Notably, while these numbers describe an entire cohort (aged 45 to 54), the changes in mortality rates were driven in particular by several subgroups. Persons with a high school diploma (or no diploma) saw a huge increase in all-cause mortality, drowning out the modest decrease in mortality for those with at least some college education. While poisonings (intentional or unintentional) and suicides increased across all geographical regions in the United States, the worst changes were observed in the West and the South.

It is possible to speculate about why people in the US, especially whites with limited education from rural or impoverished regions would be suffering. Wage increases in the United States have stagnated, and in fact inflation-adjusted salaries in 2014 are still lower than they were in 1970 Long-term economic security has declined, since the United States has moved mostly to 401k plans with associated market risks, while in Europe pensions are still the norm (p. 15081). Meanwhile the disparities in income between the rich (especially the very rich) and the poor have widened enormously over the last 35 years, leading not only to not only poverty but to resentment for those not among the rich minority. The resulting feelings of anger and insecurity might lead to scapegoating (notably of immigrants), rejection of existing power structures (especially those viewed as the elites), and a desire for an authoritarian strongman walk back these recent changes.

A cohort of white, less-educated males who are economically desperate, however, is not sufficient by itself as an explanation for the election of Donald Trump. The last piece is described beautifully in Matt Taibbi’s recent book “Insane Clown President”, in which the following argument as outlined: Televised news has gone from being a public service to a profit-making business, and a proliferation of different viewpoints have resulted in a nation in which there are a progressively smaller store of facts upon which everyone agrees. In particular for-profit news outlets have helped convert elections into ostentatious spectacles devoid of substantive policy discussions, and the officials thus elected inevitably serve only the desires of the persons who funded their elections, namely corporations and the moneyed class. The remainder of the people correctly perceive that they are frequently misled and lied to, and they have learned to distrust the well-educated class, including politicians, bankers, and journalists. In 2015 Donald Trump announces his presidential candidacy, explaining that he is not a politician, that he scorns the bankers and despises journalists. His explanations resonate with the populace. In this culture of resentment elections devolve into merely a question of who is hated less, and the number of people who hated the unambiguously establishment-friendly candidate Hillary Clinton was roughly equivalent to the number of people who hated Donald Trump. The coin flip went to in the wrong direction for Hillary Clinton and now Donald Trump has become president.

I keep looking for the historical precedent which might make this year seem less unprecedented and ahistorical. At first I was looking at the 1870s and reconstruction, when the KKK was first formed in the American South as a reactionary response to the prospect of un-enslaved black people. Then I thought we might be reliving the 1920s, when social mores changed too quickly for many, and when the KKK was again resurgent. But after seeing Trump’s inauguration speech I became convinced instead that we are reliving 1968, with Trump reprising Richard Nixon’s law and order theme, and seeking to speak for the Silent Majority in all but name. (Taibbi makes this comparison too, and with the many outstanding lawsuits against Trump and with Nixon’s well-known fall due to flagrant illegalities it is hard not to see the parallels). In addition to convincing me that US culture in 2016 has not completely run off the rails, however, those earlier historical periods have something else to tell us. When a previously dominant group became less powerful and more desperate, and when rapid social change led people to feel destabilized, then the traditional outlet for the resulting resentments is racism and scapegoating. So maybe the current ugliness that demeans our society is only a temporary affair, and one which will ultimately be replaced with increasing tolerance and pluralism.

Image credits:

References:

- . Rising morbidity and mortality in midlife among white non-Hispanic Americans in the 21st century PNAS, Volume 112, no. 49, December 8, 2015. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1518393112

- , Insane clown president Spiegal & Grau, 2017, ISBN: 0399592466